India's grassroots innovators come up with amazing solutions through their own ingenuity. But I often wonder how much more innovation they would be able to do if only they had access to better education in their

formative years.

The

long-term solution to this is, of course, clear - improve the quality of school

education across the country. But, the

gap between single classroom schools that characterize much of the government

school system in rural India, and effective science education seems so wide

that it is easy to despair about how long this will take.

Fortunately,

some alternate models are at hand. On January 30, I had the privilege of visiting

the Agastya Foundation's main science centre near Kuppam, a small town at the

confluence of 3 states - Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

The Agastya International

Foundation Science Centre at Kuppam

In 2011-12,

about 75,000 students from government schools in the vicinity of Kuppam and

private schools visited this centre. Here, they attended science classes

integrated with practical demonstrations that they would never be able to see

in their own schools; were exposed to puzzling scientific phenomena; and even took

apart bicycles and ceiling fans to put them together again. The more curious

among them got a chance to work on their own ideas, many of which were

developed with the help of the facilitators into concepts entered for

innovation contests like IRIS and IGNITE.

The Centre

also serves as a training ground for teachers - they have their own training

sessions while their students are engaged in the Agastya experience.

An in-house

workshop designs and fabricates apparatus for new experiments, or replicates

apparatus for use in smaller science centres elsewhere and the 67 mobile

science vans that take the excitement of science learning to school students

across 10 states of India.

How well

does it work?

The

experiments are well designed. Many of them can be done by students themselves.

A signboard of dos and don’ts reads “Do touch and play” instead of the “Don’t

touch” sign you would expect to see in a typical museum. That pretty much

summarises the Agastya philosophy.

I found the

hundreds of students at the centre (about 500-600 visit on a typical day) from

government schools (girls and boys alike – I was relieved to see that Agastya

has equal numbers of both!) involved with rapt attention in what was going on.

(In contrast, I saw some of the students from urban private schools looking a

tad disengaged - I was told that this was because their schools allow them to

choose what they "like" and "don't like"!). Of course,

learning science takes time – in the Chemistry class I visited, the instructor asked

the students where in their homes they would find a Chemistry lab, but few

could identify the place where their food was cooked as the answer.

Students who

visited Agastya have been doing very well in national innovation contests. At the

Initiative for Research and Innovation in Science (IRIS), a joint initiative of

the Department of Science & Technology, CII and Intel, their concepts have

been regularly short-listed at the final stage, and 2-3 projects have been winning

prizes every year. One such award went to a team that developed a project on

larvicidal activity of citrus fruit peel oil after the mother of one of the

students suffered a particularly painful attack of Chikungunya!

2 students

who have been through Agastya's programmes have been admitted to IITs.

Many of the student

projects have an ecological flavor to them. The Agastya staff attributed this

to the students coming from a rural background. But it is my experience that current

students from diverse backgrounds are all much more committed to ecology and

sustainability concerns than the generations that preceded them.

The Agastya

campus is on a picturesque yet dry 100+ acre campus with distinctive

architecture and views which add to the student experience.

There were

very few discordant notes at Agastya. Credit for this should go to founder

Ramji Raghavan and his committed team. Balaram, the campus manager who showed

us around clearly took tremendous pride in his job, and the philosophy of

Agastya. Though his education was in arts and law, he has a good understanding

of all the experiments and has imbibed the Agastya philosophy as well.

My only crib

was that most of the charts and documentation were in English though it was

apparent that many of the kids would struggle to read the language. Over time,

the students need to be exposed to relatively contemporary exhibits and

experiments in electronics and information technology as well (a new IT

building is close to completion, so the IT learning should start soon). And,

hopefully, there will be more learning that transcends disciplinary boundaries.

How Scalable

is the Agastya Model?

The Kuppam

facility itself is a sprawling campus, and the capital expenditure in setting

up such a campus would be very large. However, smaller science centres based on

the Kuppam model can be created at reasonable costs. Already, Agastya

Foundation has set up such centres across Karnataka. Other states including

Bihar and Punjab are seriously considering adopting the Agastya model. The

science vans are the other way of diffusing the learning process – each science

van carries a set of exhibits and experiments and typically spends a day at a

rural school. Agastya trains instructors to work in the science centres as well

as the vans.

While the

ultimate dream would be to have every school in India with a well-equipped

science lab, in the interim the Agastya model could work well. Agastya’s

commitment to science education and their interest in scaling up makes this more

likely to succeed compared to setting up labs in all schools and training all

teachers. In many places, I would imagine that government school teachers would

tend to keep all apparatus locked up for fear that they would stop working or

be damaged or stolen leading to audit and other questions! We asked

Shibu, the head of the Kuppam facility how teachers viewed Agastya – he explained

that they were happy to see their students learn things in a more practical way

though they tended to find it difficult to keep up with the students’ questions

after a visit to a science centre!

I was really happy to see an art classroom in this science centre complex. As C.P. Snow observed in his classic on the two cultures, science and arts often get divorced from each other, to the detriment of both.

I was really happy to see an art classroom in this science centre complex. As C.P. Snow observed in his classic on the two cultures, science and arts often get divorced from each other, to the detriment of both.

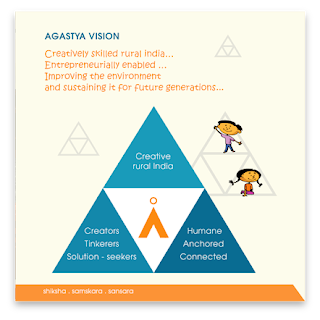

Agastya Foundation’s efforts mark an important step towards kindling creativity and innovation across the length and breadth of India.

This is a commendable effort. In addition to spreading the education, it would be good to make student create the scientific apparatus in course of their study. Emphasis should be on using commonplace items for this. This will then make them love the apparatus and reduce dependence on purchased equipment.

ReplyDeleteThis may require slight modification in the way experiments are done. For example, it may be difficult to make a accurate weighing machine, but this can be replaced by volumetric measurement instead. Or maybe use a commonplace resistances instead of a resistance box in physics laboratory.

how can i learn more about agastya,i am interested in joining my child please let me know the details of your programme

ReplyDelete